Understanding Music Royalties

Foundations of Music Royalties under UK Law

The question of how music royalties are understood, allocated, and enforced under United Kingdom law has been the subject of extensive legal and commercial debate for decades. The framework touches upon multiple branches of law including contract, intellectual property, equity, and commercial practice. For working musicians, the consequences of properly understanding royalties are not merely academic but directly influence their livelihood, bargaining power, and long term financial stability. This section seeks to set out the foundational principles of music royalties within the UK legal landscape, grounding the discussion in contract law, statute, and case law, while also illustrating these rules through practical scenarios that musicians will recognise from their day to day professional experiences.

At its core, a royalty is a contractual payment made by one party to another for the use of an intellectual property right. In the music industry, royalties arise in various forms: performance royalties for the public communication of works, mechanical royalties for reproduction of works in physical or digital form, synchronisation royalties for the placement of music with visual media, and equitable remuneration for certain uses established under statute. The underlying right that generates a royalty is typically copyright, as codified in the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA). Section 16 of the CDPA establishes the acts restricted by copyright, and any unauthorised performance or reproduction triggers the need for licensing, which in turn produces a royalty obligation.

While copyright is the statutory foundation, royalties themselves are enforced largely through private agreements. Contract law, therefore, plays the central role in determining how royalties are calculated, distributed, and contested. For example, when a songwriter enters into a publishing agreement, the terms will specify how mechanical royalties from streaming or physical sales are to be divided between publisher and writer. Similarly, when a band signs are cording contract with a label, the contract will stipulate the royalty percentage payable on net receipts or on the dealer price of recorded music. The terms of those agreements are governed by ordinary principles of English contract law, drawing upon centuries of jurisprudence from Partridge v Crittenden [1968] 2 All ER 421 on offers and invitations to treat, through to Photo Production Ltd v Securicor Transport Ltd [1980] AC 827 on the effect of exclusion clauses.

The fundamental doctrine of freedom of contract, affirmed in Printing and Numerical Registering Co v Sampson (1875) LR 19 Eq 462, underpins music royalty agreements. Parties are generally free to agree whatever royalty formula they wish, subject to statutory limitations. This freedom is double edged. On the one hand, it allows musicians with bargaining strength to secure favourable terms, for example higher royalty percentages or advances against royalties. On the other hand, it exposes inexperienced musicians to the risk of signing contracts that are disproportionately weighted in favour of labels or publishers, with long recoupment clauses or royalty deductions that erode the practical value of the income stream.

To illustrate, consider the situation of a four piece independent band who sign their first recording contract with a mid level UK label. The contract offers a15 percent royalty on net receipts from album sales. At first glance, 15percent may appear generous, but the contract also includes clauses permitting the deduction of packaging charges, promotional costs, and tour support from the royalty base. In practice, after deductions, the band may receive little or no royalty income despite significant sales. Such an outcome reflects the legal principle that the courts will uphold clear contractual wording even if the bargain is onerous, provided there has been no misrepresentation, duress, or undue influence. This was confirmed in L’Estrange v Graucob[1934] 2 KB 394, where the Court of Appeal held that a party who signs a contractual document is bound by its terms regardless of whether they have read or understood them. For musicians, the lesson is stark: the royalty structure is enforceable as written, unless grounds for vitiation of the contract can be established.

Royalty disputes often arise where the contractual wording is ambiguous. English courts apply the rules of interpretation set out in Investors Compensation Scheme Ltd v West Bromwich Building Society [1998] 1 WLR 896, where Lord Hoffmann articulated the modern approach. Contracts are interpreted in accordance with the meaning that a reasonable person with the background knowledge reasonably available to the parties would have understood. Thus, if a contract provides that “royalties are payable on net receipts,” but does not define whether promotional copies or discounted sales count towards net receipts, the court will interpret the clause in light of commercial common sense and the factual matrix. In music industry practice, ambiguity frequently arises around deductions, audit rights, and digital streaming revenue, all of which hinge upon careful contractual drafting.

Statutory intervention plays a complementary role. Under section 182D of the CDPA, performers are entitled to equitable remuneration when commercially released sound recordings are played in public or broadcast. This entitlement is collected in the UK by PPL and distributed to performers, regardless of whether they have entered into a private contract with the record label. This statutory right provides a baseline protection for working musicians, ensuring that even session players receive payment when recordings are exploited. The House of Lords in Performing Right Society Ltd v Harlequin Record Shops Ltd [1979] AC1 reinforced the principle that public performance of music requires licensing, which gives rise to royalties payable to rights holders.

Equally important are the competition law considerations that overlay collective licensing practices. The Competition Act 1998 and articles of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (still of interpretive relevance post Brexit) impose limits on the market behaviour of collecting societies such as PRS for Music and PPL. These societies manage the flow of performance and mechanical royalties, and their contractual frameworks must comply with competition law to avoid abuse of dominant position. Case law such as British Horseracing Board v William Hill Organisation Ltd [2001] RPC 31 demonstrates how intellectual property rights interact with competition principles, offering analogies for the licensing of musical works.

From a practical standpoint, musicians must appreciate the dual nature of royalties: they are both a statutory entitlement in certain circumstances and a contractual entitlement in others. Failure to understand this duality leads many to neglect the opportunities available through collective rights management. For instance, a self released artist who distributes music digitally might assume that royalties only arise if a contract with a label exists. In fact, streaming platforms such as Spotify or Apple Music are licensed through PRS and MCPS for the use of compositions, and through PPL for the use of recordings, generating royalties independently of any label contract.

Another practical scenario arises in the field of synchronisation licensing. Suppose a songwriter agrees to license a track for use in a UK television advert. The royalty agreement specifies a one off synchronisation fee plus a share of performance royalties through PRS. If the advertiser later places the advert on global streaming platforms, questions may arise as to whether additional royalties are due. Under the principle in Hadley v Baxendale (1854) 9 Exch341, damages or obligations for breach are recoverable only for losses that were within the reasonable contemplation of the parties at the time of contracting. Thus, unless the contract explicitly contemplated global digital exploitation, the songwriter may struggle to claim additional royalties beyond the agreed synchronisation fee and performance share. This highlights the importance of anticipating technological and territorial developments within royalty contracts.

Musicians should also recognise the impact of equitable doctrines. Where a contract is silent or ambiguous, the courts may imply terms to give the contract business efficacy under the rule in The Moorcock (1889) 14 PD 64. For instance, if a publishing agreement fails to specify a payment mechanism for mechanical royalties, the court may imply a term that payment must be made within a reasonable time and according to industry custom. Similarly, under the doctrine of unjust enrichment, a musician may claim restitution where another party has profited from the unauthorised exploitation of their work without a contractual basis.

Inconclusion, the foundation of music royalties in UK law rests upon a blend of statutory rights, contractual freedom, and interpretive doctrines. For working musicians, the crucial lesson is that while copyright law creates the right to remuneration, it is contract law that largely determines how those royalties are realised in practice. Statutory interventions provide certain safety nets, but the primary safeguard remains careful negotiation and drafting of contracts. Musicians who fail to engage with the legal foundations risk finding themselves bound by unfavourable royalty structures that the courts will uphold with strictness. The practical message is clear: every clause matters, every definition matters, and every deduction matters. Understanding royalties begins with understanding the law that shapes them.

Royalty Disputes, Enforcement, and Remedies under UK Law

Disputes over music royalties are a defining feature of the UK entertainment industry, not because the law lacks clarity, but because the interaction between complex contracts, evolving technology, and commercial pressures inevitably gives rise to disagreements. For musicians, these disputes can be existential. Royalties are often their only long term income stream, and when disputes arise, they can mean the difference between financial survival and collapse. This section examines how such disputes manifest, the legal mechanisms available for enforcement, and the remedies courts and tribunals may award. It will analyse the leading principles of contract law, equitable relief, and statutory provisions, while also illustrating how these doctrines play out in the lived experiences of musicians.

At the heart of many disputes is the issue of contractual interpretation. As established in Investors Compensation Scheme Ltd v West Bromwich Building Society [1998] 1 WLR 896, contracts are interpreted in light of the objective meaning of their language within the context of the agreement as a whole. This principle becomes critical in royalty cases, where definitions of “net receipts,” “deductions,” or “advances” can determine millions in revenue. Musicians frequently challenge royalty statements provided by labels or publishers, alleging under reporting or improper deductions. In such disputes, the courts will examine whether the contract expressly permits the contested practice. For example, if a contract allows deduction of “reasonable promotion expenses,” but the label deducts the full cost of international touring, a court may find the clause does not extend that far. The commercial common sense approach, endorsed in Rainy Sky SA v Kook min Bank [2011] UKSC 50, empowers courts to favour an interpretation that avoids absurd or commercially irrational results, although this is applied cautiously to preserve contractual certainty.

Enforcement begins with contractual mechanisms. Well drafted royalty agreements usually contain audit clauses entitling musicians to inspect the label’s accounts. Such clauses are vital, as they provide the evidential foundation for any claim. In the absence of an audit clause, musicians must rely on general disclosure obligations in litigation, which are less efficient and more costly. Disputes frequently centre on whether the label has complied with the audit process, whether the auditor was given full access, and whether accounting practices were consistent with industry standards. In Compagnie Noga d’Importation et d’Exportation SA v Australia and NewZealand Banking Group Ltd [2002] EWCA Civ 1142, the Court of Appeal affirmed the importance of contractual audit rights, holding that refusal to comply could amount to a repudiatory breach. Applied to music royalties, if a label obstructs audit rights, the musician may have grounds not only for damages but potentially for termination of the contract.

Once a breach has been established, remedies under English contract law come into play. The default remedy is damages designed to put the claimant in the position they would have been had the contract been properly performed, as established in Robinson v Harman (1848) 1 Exch 850. For royalty disputes, this usually means payment of the underpaid royalties plus interest. Interest is generally calculated under the Late Payment of Commercial Debts(Interest) Act 1998, which provides a statutory right to interest at eight percent above the Bank of England base rate where the debt arises under a commercial contract. This statutory regime can be particularly advantageous to musicians, as late royalty payments often stretch over years, leading to significant accumulations of interest.

In some cases, damages may be inadequate. For example, where a label persistently underreports royalties, the musician may seek an injunction to compel accurate accounting. While courts are traditionally reluctant to grant specific performance of contracts involving ongoing obligations, they have discretion todo so where damages would be insufficient. In Warner Bros Pictures Inc vNelson [1937] 1 KB 209, the court restrained the actress Bette Davis from working for other studios in breach of contract, illustrating the willingness to grant equitable relief in entertainment contexts. In royalty disputes, an analogo us order might compel compliance with audit clauses or restrain further exploitation until proper royalties are paid.

Another area of contention arises when musicians allege that royalty agreements are unfair or oppressive. English law does not permit courts to rewrite bad bargains, but there are limited doctrines available. One is misrepresentation, where false statements induced the contract. If a label exaggerated expected sales or misrepresented the scope of deductions, the musician may have a claim for rescission or damages under the Misrepresentation Act 1967. Another is undue influence, though this is harder to establish in commercial contexts. More relevant is the doctrine of restraint of trade. In Esso Petroleum CoLtd v Harper’sGarage (Stourport) Ltd [1968] AC 269,the House of Lords recognised that excessively long contracts restraining commercial freedom may be unenforceable. Applied to music, a contract locking a band into unfavourable royalties for decades may be vulnerable if it can be shown to unduly restrain their artistic and commercial liberty.

The Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 and the Consumer Rights Act 2015 also play a role, though their scope is limited in music royalty disputes. Most musicians contracting with labels or publishers are acting in the course of business rather than as consumers, meaning consumer protections do not apply. However, smaller or less sophisticated musicians may argue that standard form contracts imposed by labels should be subject to scrutiny for unfair terms. The courts remain cautious, but there is a growing recognition of the imbalance of bargaining power in the creative industries.

Practical examples illustrate these doctrines vividly. Consider a songwriter who signs a publishing agreement entitling them to fifty percent of mechanical royalties. Years later, the songwriter audits the publisher and discovers that streaming royalties have been classified as “licence income” subject to higher deductions, rather than as mechanical royalties. The songwriter challenges this under the contract, arguing that streaming is a form of reproduction covered by the mechanical royalty clause. The dispute turns on contractual interpretation. If unresolved, it proceeds to litigation, where the court applies the ICS principles and may side with the songwriter if commercial common sense supports their view. The remedy would be payment of the underpaid royalties plus interest.

Another scenario involves a session musician who contributes to a recording but is denied equitable remuneration when the recording is broadcast. Under section182D of the CDPA, the musician has a statutory right to remuneration regardless of contract. If the label refuses to register the performer with PPL, the musician can bring a claim for statutory breach. The court will enforce the statutory entitlement directly, illustrating how remedies may derive from statute as well as contract.

Enforcement also raises issues of jurisdiction and cross border royalties. In today’s global streaming market, royalties are often generated in multiple territories. Disputes can arise as to whether UK courts have jurisdiction over royalties collected abroad. The Brussels Regulation regime continues to influence jurisdictional questions, even post Brexit, with English courts applying forum conveniens principles to determine whether proceedings should be heard in the UK. In practice, many contracts include exclusive jurisdiction clauses in favour of English courts, which the courts generally uphold under Fiona Trust & Holding Corporation vPrivalov [2007] UKHL 40. Musicians must therefore be mindful of jurisdiction clauses when entering contracts, as they determine where disputes over royalties will be litigated.

Arbitration and alternative dispute resolution are increasingly prevalent in royalty disputes. Many industry contracts include arbitration clauses, recognising the expertise of specialist arbitrators and the confidentiality of proceedings. Arbitration can be faster and less public than litigation, which is appealing to musicians who may not wish their financial arrangements exposed in open court. The Arbitration Act 1996 provides the statutory framework, and awards are enforceable in the same way as court judgments. However, arbitration can be costly, and smaller musicians may find it prohibitive without collective support. Mediation also plays a growing role, with industry bodies often facilitating settlement before litigation escalates.

Itis also worth noting the equitable doctrine of account of profits. Where a label has exploited music without proper authorisation, the musician may been titled not merely to royalties but to the label’s profits from the infringement. This principle was confirmed in Attorney General v Blake [2001] 1 AC 268, where the House of Lords allowed a restitutionary award of profits in exceptional circumstances. While rare, this remedy could apply where a label deliberately and flagrantly exploited works outside the scope of a licence.

For working musicians, the lessons are practical. First, they should ensure their contracts contain robust audit rights and mechanisms for dispute resolution. Second, they must monitor royalty statements carefully and act swiftly if discrepancies arise, as claims may be barred by limitation periods under the Limitation Act 1980. Third, they should consider collective action through societies such as PRS and PPL, which can enforce rights more effectively than individuals. Fourth, they must weigh the costs of litigation against the potential recovery, recognising that remedies may include not only damages but also interest, injunctions, and even restitutionary relief in exceptional cases.

Ultimately, royalty disputes are an inevitable by product of an industry where creative labour is monetised through complex legal instruments. English law provides a robust framework for resolving these disputes, grounded in contract, statute, and equity. Yet the effectiveness of enforcement depends on musicians’ awareness of their rights and their willingness to assert them. The courts will not rewrite contracts to rescue musicians from poor bargains, but they will enforce rights with rig our where breaches occur. For musicians, the key is to approach royalties not as a matter of vague artistic entitlement but as a matter of precise legal obligation, enforceable through well established doctrines and remedies.

Future Challenges and Practical Guidance for Musicians in the Digital Age

The landscape of music royalties in the United Kingdom continues to evolve as rapidly as the industry itself. While the foundations of royalty law lie in statute and contract, the practical realities of collecting and enforcing royalties have shifted dramatically with the rise of digital streaming, user generated content, global licensing platforms, and the decentralisation of distribution. For working musicians, these changes bring both opportunity and risk. This section examines the challenges that lie ahead, grounding the analysis in legal principles, case law, and statutory developments, and then offering practical guidance on how musicians can safeguard their financial interests in this changing environment.

The first major challenge arises from the transformation of revenue streams. Physical sales, once the cornerstone of royalty income, have declined sharply. The bulk of royalty income now flows from digital streaming services. Yet streaming royalties are notoriously complex and often opaque. Contracts signed before the advent of streaming frequently fail to address how such income should be classified. Is it mechanical income arising from reproduction, performance income arising from communication to the public, or licence income arising from platform agreements? The classification directly affects the percentage payable to musicians. Courts faced with such disputes will apply principles of interpretation as in Arnold v Britton [2015] UKSC 36,where the Supreme Court emphasised the primacy of contractual wording even if the outcome appears commercially harsh. This strict approach means musicians tied to pre digital contracts may struggle to secure a fair share of streaming royalties unless the courts can interpret wording expansively in line with commercial common sense.

Legislative intervention has attempted to modernise this framework. The UK Government, responding to industry pressure, has considered reforms inspired by European Union initiatives such as the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (Directive (EU) 2019/790). Although the UK is no longer bound to implement EU directives post Brexit, the influence remains. Article 18 of the Directive requires that authors and performers receive appropriate and proportionate remuneration when works are exploited. While this principle has not been fully embedded into UK law, it may inspire future reforms under the CDPA. If enacted, such provisions could strengthen musicians’ rights to claim additional remuneration where contractual royalties prove disproportionately low compared to revenue generated. The principle echoes equitable doctrines of fairness but would embed them in statute, potentially altering the balance of power in royalty negotiations.

Another significant development concerns transparency. Section 191H of the CDPA already requires record producers to account to performers for equitable remuneration. However, in the digital age, musicians often complain of opaque accounting practices by platforms and intermediaries. Proposals have been made to introduce statutory transparency obligations on labels and publishers, requiring regular, detailed royalty statements. Comparable obligations exist in other jurisdictions, and the UK may follow suit. Case law such as Yam SengPte Ltd v International Trade Corporation Ltd [2013] EWHC 111 (QB), which recognised implied duties of good faith in relational contracts, may also be deployed by musicians seeking greater transparency. Royalty agreements, often long term and reliant on trust, are prime candidates for such relation alanalysis, and courts may increasingly imply obligations of honesty and disclosure in their performance.

Globalisation also raises complex jurisdictional challenges. With music streamed worldwide, royalties are collected by foreign societies and subject to local laws. Musicians may struggle to track and enforce entitlements across multiple territories. Exclusive jurisdiction clauses may limit them to the English courts, but enforcement abroad remains a hurdle. The enforcement of judgments post Brexit, while still possible under common law, is less streamlined than under the Brussels regime. Musicians and their advisers must therefore anticipate cross border issues at the contracting stage, possibly negotiating clauses that require local accounting or engagement with international collection societies.

Emerging technologies create further uncertainty. The rise of blockchain and nonfungible tokens (NFTs) has prompted debate over new models of royalty distribution. Smart contracts embedded in blockchain platforms could in theory guarantee automatic royalty payments upon each use of a work. However, these arrangements still rely on underlying copyright law, and disputes may arise where the blockchain contract conflicts with traditional publishing or recording agreements. English courts, applying the doctrine of incorporation and construction, would need to reconcile digital smart contracts with existing contractual frameworks. Musicians must therefore exercise caution before entering blockchain based royalty arrangements, ensuring they do not inadvertently surrender rights already committed under traditional contracts.

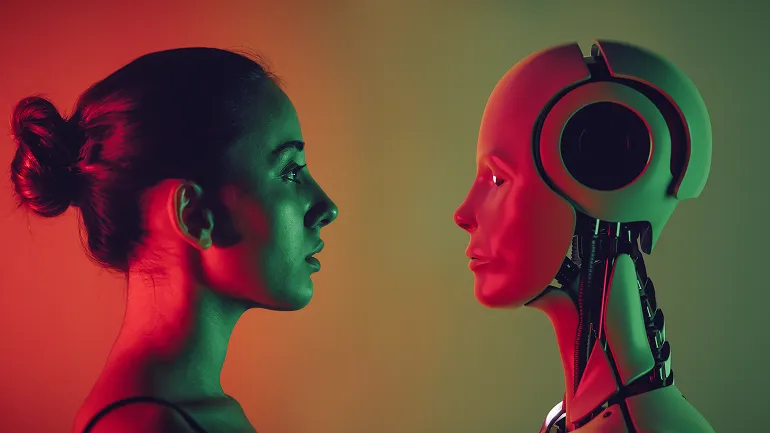

Artificial intelligence (AI) presents a different challenge. With AI generated music proliferating, questions arise as to whether royalties are payable for works created partly or wholly by machines. Under the CDPA, section 9(3) provides that the author of a computer generated work is the person who makes the arrangements necessary for its creation. This provision, unique in its scope, could result in AI developers claiming authorship and thereby royalties. For musicians collaborating with AI platforms, the allocation of royalties must be carefully negotiated. Absent clear agreement, disputes may arise as to whether the musician’s input constitutes authorship or performance under the Act. Courts will likely apply established doctrines of authorship, performance, and originality, but uncertainty will remain until case law develops.

From a practical perspective, musicians must prepare themselves through robust contracting. First, they should ensure that contracts explicitly address digital exploitation, including streaming, downloads, user generated content platforms, and future technologies. Failure to do so leaves them vulnerable to strict interpretation under cases like Arnold v Britton, which privilege clear wording over equitable outcomes. Second, they should negotiate audit rights that extend to digital exploitation. Without the ability to inspect platform accounting, musicians cannot verify whether royalties have been correctly calculated. Third, they should seek to include reversion clauses or termination rights after a defined period, protecting them from indefinite commitments that may become oppressive as technologies change. The doctrine of restraint of trade, while limited, may assist in extreme cases, but proactive contracting is more reliable.

Education and collective bargaining are equally vital. Many musicians lack the bargaining power to negotiate favourable terms individually. However, through membership of collecting societies such as PRS, PPL, or the Musicians’ Union, they can leverage collective strength. These bodies also provide dispute resolution services, legal advice, and lobbying power. Case law such as Associated British Picture Corporation Ltd v Wednesbury Corporation [1948] 1 KB 223demonstratesthe courts ’deference to administrative discretion, which has parallels in the way collecting societies manage rights. Musicians who participate actively in these societies can influence policy, ensuring that collective licensing frameworks evolve to reflect their needs.

An example illustrates these dynamics. Consider a young singer songwriter who distributes music through a digital aggregator. The aggregator contract specifies that royalties from streaming platforms will be shared seventy percent to the musician and thirty percent to the aggregator. However, the aggregator also deducts “administrative fees” without definition. When the songwriter queries the deductions, the aggregator provides vague statements. Lacking an audit clause, the songwriter has little recourse. If brought to court, the dispute would likely turn on contractual interpretation, and absent clear language to the contrary, the court may allow the deductions. Had the songwriter secured audit rights and clearer definitions, enforcement would have been far stronger. This example highlights the critical importance of proactive negotiation at the outset.

Another scenario involves a veteran session drummer who contributed to recordings in the 1990s. With those recordings now streamed globally, the drummer seeks equitable remuneration under section 182D CDPA. The label argues that streaming is not a “broadcast” or “public performance” but a communication outside the statutory scope. Courts faced with such a dispute will need to interpret the statute purposively, considering technological change. The principle in Pepper v Hart[1993] AC 593,allowing reference to parliamentary materials, may be invoked to ascertain legislative intent. Ultimately, courts may conclude that streaming falls within“ communication to the public,” ensuring equitable remuneration continues to apply in the digital age. This demonstrates how statutory interpretation evolves to protect musicians even in new technological contexts.

Looking ahead, musicians must also consider the limitation of claims. Under the Limitation Act 1980, actions for breach of contract must generally be brought within six years. Many musicians only discover underpayment of royalties decades later, when audits finally occur. The doctrine of concealed fraud undersection 32 of the Act may extend limitation where wrongdoing was deliberately concealed, but this is difficult to prove. Musicians should therefore act promptly upon discovering discrepancies, seeking legal advice and commencing proceedings before limitation bars their claims.

Finally, musicians must adopt a mindset that views royalties not as a passive entitlement but as an actively managed asset. Just as a property owner manages rent, musicians must monitor, enforce, and renegotiate royalties. This requires legal literacy, collective organisation, and strategic contracting. The courts will enforce their rights, but only where those rights are clearly defined and properly asserted. Equity will intervene in limited cases, and statutory reforms may enhance protection, but the primary safeguard remains the musician’s own diligence.

Inconclusion, the future of music royalties in the UK lies at the intersection of law, technology, and practice. The courts will continue to apply established doctrines of contract interpretation, equitable remedies, and statutory construction. Legislators may enhance fairness through reforms addressing transparency and proportional remuneration. Technology will create new opportunities and risks, requiring careful adaptation of legal frameworks. For working musicians, the path forward is clear: understand the law, negotiate contracts with foresight, engage collectively, and treat royalties as a professional asset requiring constant vigilance. By doing so, they can secure their place in an evolving industry, ensuring that their creative labour continues to generate fair and sustainable income.

Our services

Commercial Partnerships & Digital Media

The modern music industry extends far beyond records and live shows. Artists increasingly rely on partnerships with brands, merchandising opportunities, synchronisation deals, and digital platforms to grow their careers and generate income. These arrangements can be highly rewarding, but without careful agreements, they can also dilute your rights or undervalue your contribution. At musiclegal.co.uk, we connect you with experienced professionals who understand how to protect your interests while unlocking the potential of commercial partnerships and digital media.

Contracts & Agreements

Every successful music career rests on clear, carefully written agreements. Contracts are not about limiting creativity but about protecting it. Whether you are an emerging artist negotiating your first management deal, a band agreeing how to share income, or a label setting out terms with a producer, written agreements ensure that expectations are understood and disputes are avoided. At musiclegal.co.uk, we connect you with experienced professionals who specialise in the music industry and understand both the business and the artistry. Our goal is to help you secure fair terms so that you can focus on the music.

Debt Recovery

Few things are more frustrating for musicians than not being paid for their work. Whether it is an unpaid gig fee, a delayed royalty payment, or a contract that has been ignored, unpaid income can create financial strain and damage trust. The music industry is fast moving, and chasing money can feel awkward or even risky if you fear losing future opportunities. At musiclegal.co.uk, we connect you with professionals who understand the realities of the industry and who can help recover what you are owed quickly, professionally, and without burning bridges.

Disputes & Conflict Resolution

The music industry is full of collaboration, but wherever there are creative partnerships there is also the potential for conflict. Disputes can arise between band members, between artists and managers, or over unpaid fees and royalties. Left unresolved, these issues can damage relationships and careers. At musiclegal.co.uk, we connect you with professionals who specialise in resolving music industry disputes quickly, fairly, and with as little disruption as possible, so that you can return your focus to the music.

Intellectual Property & Rights Protection

.webp)

Every piece of music begins as an idea, and that idea is intellectual property. Protecting it is the difference between retaining control over your work and watching it slip away. Copyright, performer’s rights, trade marks and brand protection all form part of the framework that allows musicians and businesses to safeguard what they create. At musiclegal.co.uk, we connect you with professionals who understand the music industry’s unique legal landscape, ensuring that your songs, recordings and identity are protected so that your career can grow securely.

Live Music, Touring & Events

The thrill of live performance is at the heart of every music career. From intimate club shows to major festival appearances, the live sector is where artists connect directly with their audience. But behind every performance sits a web of agreements covering payment, cancellations, liability, insurance, and logistics. Without proper documentation, artists risk financial loss, disputes with promoters, or even cancelled shows. At musiclegal.co.uk, we connect you with professionals who ensure that your live music contracts are clear, fair, and built to protect you, so you can take the stage with confidence.

Royalties, Publishing & Revenue Streams

.webp)

Royalties and publishing are the lifeblood of many music careers. They represent the money that flows when your music is played, performed, streamed, sold, or used in film and advertising. Yet the systems that govern royalties are notoriously complex, often leaving musicians underpaid or uncertain about what they are owed. At musiclegal.co.uk, we help you understand how revenue streams work, how to protect your rights, and how to make sure that you receive fair payment for your creative efforts.

.svg)

.webp)

.webp)